Save The Powerhouse

The Powerhouse is a pivotal Jersey City landmark and cultural heritage site that preservationists have been fighting to save for over 25 years. The 117-year-old industrial monument — long vacant and tragically uncared for — is a rare and intact specimen from an age of great architectural and engineering ambition and inventiveness.

When the Powerhouse was awakened in 1908 by a telegram signal triggered by President Theodore Roosevelt, electric current circulated through the entirety of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad’s groundbreaking electric railcar network (now PATH), a pioneering project first started by Dewitt Clinton Haskins in 1873 at the foot of 15th Street and finally brought to fruition in 1908 by the visionary William Gibbs McAdoo. In 1962 the Port of New York Authority acquired the bankrupt Hudson & Manhattan Railroad system and its architectural assets and since 1965 has operated a large substation and transformer apparatus yard at the Powerhouse site.

In 1999 a group of activist citizens was organized in Jersey City and immediately incorporated as a non-profit 501(c)(3) preservation organization with the primary reach of preserving, protecting and reviving the Powerhouse, today surrounded and flanked by 21st century supertall skyscrapers and other overscaled developments.

Continuing the battle, the Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy has advanced its Save the Powerhouse campaign with a new sense of hope, confidence and energy. We hope to bring awareness to the structure’s history, engage residents, garner local and national support, and organize around a supportive community.

Above Video: Reena Rose Photography | Watch entire video HERE

Do you want to help save the Powerhouse?

Join our growing community of advocates. We’ll keep you updated on upcoming initiatives, events, and ways you can take action to bring new life to this landmark!

Timeline of the Powerhouse

1850

Visions of an extensive sub-aqueous steam-engine rail system connecting the increasingly dense and industrialized coastal cities of Hudson County with Manhattan Island started appearing in newspapers and editorials.

1873-1874

The Hudson Tunnel Railroad Company was established by Col. DeWitt Clinton Haskins (circa-1824-1900), the manager of a crew of “sandhogs” in the sinking of a shaft at the foot of 15th Street in the Horseshoe tenement ward of Jersey City. Injunctions by local competing railroads, however, successfully stopped construction for the next 5 years..

1878

Powerhouse architect John Oakman (1878-1963) was born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. He would go on to have an illustrious career as an architect of sophisticated industrial, institutional and residential architecture and serve valiantly in the American Ambulance Corps and the American Expeditionary Forces in France during World War I. Oakman’s marriage to Margaret Curzon Marquand (1870-1948) would bring him into contact with American novelist John Phillips Marquand (1893-1960), who modeled several characters in his award-winning novels on the Oakmans, including the brilliant architect (and injured soldier) John Oakman.

1879-1880

After numerous court proceedings and agreements, Haskins finally resumed construction at the shaft, utilizing new air-compressed tunneling and shield-lining methods that would soon prove to be an untested and unstable method — and tragically unsafe. The shaft was sunk an amazing 60 feet below the sandy surface, but on July 21, 1880, the river suddenly crashed through the bored segment, instantly drowning twenty workers, including Jersey City foreman Peter Woodland, who is buried in New York-Bay Cemetery on Garfield Avenue in the Greenville district of Jersey City.

1881-1901

Work resumed on and off on the system over the next two decades, with engineering advancements from England being utilized to push the tunneling forward. Due to a continuous string of financial issues — lack of investors, foreclosures, liens — the project often stalled, stopped, resumed, and stopped again, finally leading to abandonment and the flooding of the semi-completed tubes.

1902-1904

William Gibbs McAdoo (1863-1941), a Georgia-born attorney with considerable experience in constructing municipal trolley lines and a rising star in New York financial and political circles, rekindled and expanded Haskins’s dormant subway vision — The Fates had marked a day when I was to go under the river-bed and encounter this piece of dripping darkness. I was destined to give it color and movement and warmth, McAdoo wrote later in his 1931 autobiography — and within a few years successfully organized banks, backers, and bondholders to form the New York & New Jersey Railroad Company, at the same time assembling a force of some of the era’s best engineers and architects to build out the system. Significant land purchases, rights-of-way, partnerships and agreements commandeered by McAdoo were quickly made, and by early 1906, with the routes and termini of the subway firmly planned and programmed for both sides of the Hudson River, McAdoo’s Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Company — the direct forerunner of what would become, in 1962, the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) system — was solidified as a transportation franchise as reaching and transformative as New York City’s Interborough Rapid Transit Company (IRT) and the Pennsylvania Railroad’s twin rail tunnel networks (now part of Amtrak and New Jersey Transit).

1906-1908

McAdoo hired Robins & Oakman, a young firm founded in 1904 by William Powell Robins (1870-1926) and John Oakman (1878-1963), both graduates of the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris. The Powerhouse, with a stunning south-north width of 230 feet, an east-west depth of 200 feet, and a height of 108 feet, was planned, constructed and completed as a fully fireproof generating current power plant between 1906 and 1908 at a staggering cost of $325,000 dollars — $13,000,000 in inflation-adjusted 2025 dollars — with civil engineering carried out by Jersey City’s James J. Ferris with additional civil, mechanical and electrical engineering by Charles M. Jacobs, A.R. Whitney Jr. & Co., John Van Vleck, L.B. Stillwell, and Hugh Hazelton. The Evening Journal of Jersey City featured a series of detailed articles from 1906-1908 reporting on the construction feats and developments of the tunnels and their supporting structures and gave much focus on its manifesting power station in Jersey City bounded by Washington, Greene, Bay and First streets — a strategic spot, as it represented the midway point in the subway system — noting: “Work on the power house ‘de luxe’…is being rushed with all possible speed in order that it may be ready for operation when the big terminal office building in New York is completed. At the Jersey City power station there will be developed the current for 3,000 incandescent lamps that will illuminate the 4,000 offices in the structure. The same power will also operate the 39 passenger elevators with which the building will be equipped.” The “Hudson Tunnels” — or, “The McAdoo Tunnels,” or “The Tubes,” as subsequent monikers would become known for years to come — was ceremoniously triggered by President Theodore Roosevelt on February 25, 1908, via an Oval Office Tiffany-silvered telegram signal plaque connecting, at the push of a button, Hoboken with Manhattan. Once turned on, the Powerhouse’s distributing conveyors, sectional 900-horse power water-tube boilers, super-heaters, huge air compressors, illumined control panels, vertical-shaft turbo-generators and spinning dominos churned out around-the-clock electricity to the H&M’s rails, attendant cars, ornamental stations, and fleets of high-speed elevators and mutli-story office lighting inside the company’s mammoth Hudson Terminal buildings in Lower Manhattan (now the exact site of the World Trade Center complex.)

1920

In 1920 the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad made the decision to immediately cease self-generating electrical current through the burning of anthracite coal and purchase power instead from outside power utilities — effectively silencing the Powerhouse and making the plant obsolete after only 12 years of use. The Powerhouse would henceforth be used merely as the system’s large equipment storage space — nothing more — and in 1965 a modernized electric transmission network would be installed in sectioned-off concrete block units inside and in a vast yard outside the building. (This important network is still in use today but is scheduled to be removed and relocated in the near future to a new adjacent substation currently under construction, a development that will free the Powerhouse from the Port Authority’s 60-year-old grip and set the stage finally for responsible and development of the site.)

1958-1962

The year-after-year-money-losing Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Company was liquidated under bankruptcy proceedings and acquired by the Port of New York Authority, the forerunner of the present-day Port Authority of New York and New Jersey. Consequently, PATH was formed in 1962 as a subsidiary of the behemoth agency, acquiring all of the H&M’s assets — including the long-inactive Powerhouse in Jersey City.

1963

Powerhouse architect John Oakman died at age 85.

1965

PATH erected and installed state-of-the-art electricity-generating transformers, compressors, switches, controls, and substation units in an adjoining yard on the west side of the Powerhouse along Washington Street; electrical equipment was also erected in a small portion of the interior of the Powerhouse. This new facility would produce power for the electric grid of the newly-established PATH system and, later, provide ground-level power to the World Trade Center complex in Lower Manhattan.

1973

The World Trade Center opened, with major sections of its below-ground subway platforms and elevators receiving partial power from the Powerhouse in Jersey City.

1978

The American Society of Civil Engineers designated the Hudson Tunnels (now PATH) a National Civil Engineering Landmark.

1999

A grassroots preservation campaign was launched in September 1999 to publicly protest fast-tracking plans by the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the City of Jersey City to demolish the Powerhouse, a citizen-empowered effort that led to the formation that same year of the non-profit Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy (JCLC). Later this same year the JCLC submitted a State & National Registers of Historic Places nomination to the New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), a move that drew vehement opposition from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the City of Jersey City, the site’s co-owners. A decision for listing on the Registers would drag out in Trenton and Washington, D.C., for several years with the Port Authority continuing its objections. The JCLC expanded and bolstered its base of support in these early years by partnering with community-empowered preservation organizations, cultural institutions, university architecture programs, arts groups, and interested citizens equally determined to stop the Port Authority and Jersey City government from destroying the Powerhouse.

2000

In the year 2000 several major advances occurred with the Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy’s Powerhouse campaign: Preservation New Jersey added the Powerhouse to its annual 10 Most Endangered Historic Places in New Jersey list; the prestigious Society for Industrial Archeology published a front-page Powerhouse feature, exposing the plight of the Powerhouse to a national audience; and, working with Jersey City-based Pro Arts, the Conservancy presented The Powerhouse Show, an expansive art exhibition at Fleet Bank’s historic headquarters (originally the First National Bank of New Jersey and now the site of Hyatt House) on the Jersey City waterfront at Exchange Place. Curated by photographer Peter Zirnis, the exhibit brought together local prominent artists working conceptually, abstractly and realistically in various mediums, including paint, photography, etching, and sculpture.

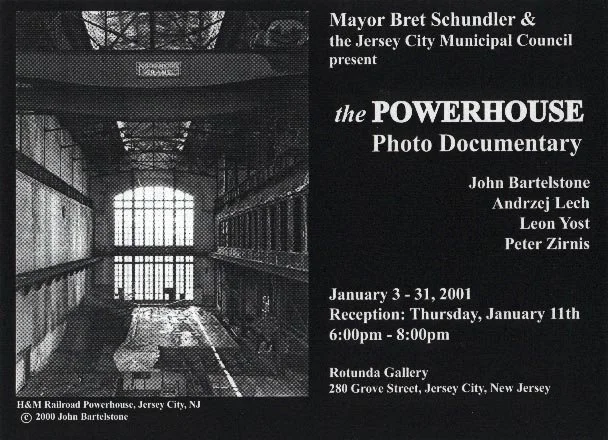

2001

The Powerhouse Photo Documentary exhibition was held in Jersey City’s City Hall Rotunda Gallery and included sublime analogue and early digital Powerhouse images by prominent photographers John Bartelstone, Andrzej Lech, Leon Yost, and Peter Zirnis. The show drew a significant crowd at its opening reception, including the descendants of William Gibbs McAdoo, the founder of the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad Company (now the PATH) who, working with gifted architects and engineers from 1906-1908, built the Powerhouse to provide power to his visionary subway system.

2001

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center site destroyed buildings, tunnels and stations once powered directly by Powerhouse-located substations and transformer yards in Jersey City. In November of 2001 — over two years after being submitted by the Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy — the Powerhouse was listed on the National Register of Historic Places, one of only two New Jersey landmarks at that time to be named to the National Register by the National Park Service despite being rejected for listing on the New Jersey State Register of Historic Places, normally a prerequisite designation before the nomination is forwarded to Washington for National Register consideration. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey and the City of Jersey City were stunned by the decision and refused to acknowledge that the Powerhouse was now a recognized (and protected) monument.

2003

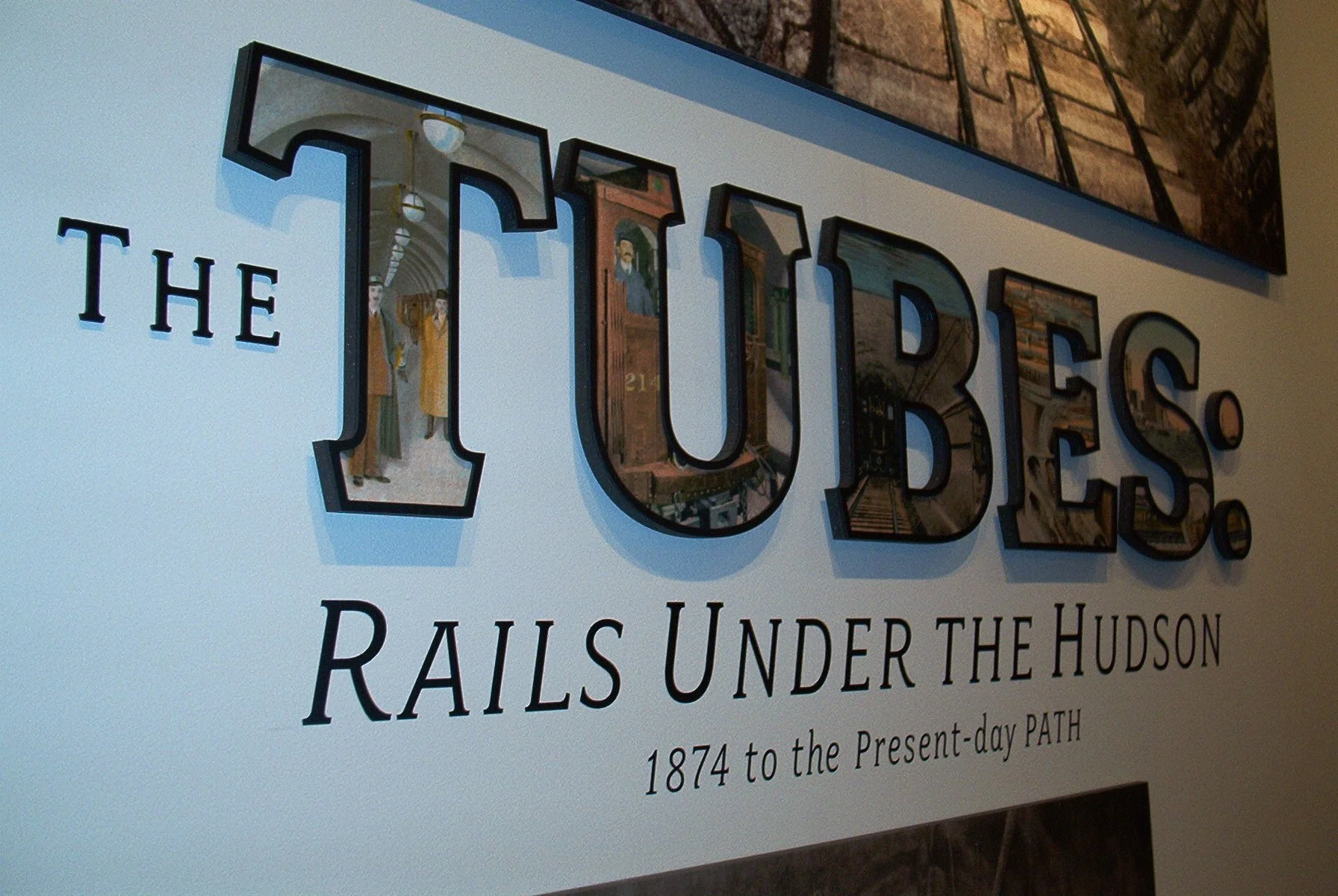

The Tubes: Rails Under the Hudson opened at the Hoboken Historical Museum featuring archives, artifacts, ephemera, documents and photographic images related to the Powerhouse and the Hudson & Manhattan Railroad (now the PATH). As part of a related lecture series, Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy founder John Gomez presented Saving the Hudson & Manhattan Powerhouse, an illustrated standing-room-only talk sharing the saga of the battle to prevent the Powerhouse’s demolition and blasting the Port Authority for its continuing neglect of the singular Jersey City landmark.

2004

Jersey City established the Powerhouse Arts District, an arts-themed residential and commercial neighborhood with affordable studio spaces set aside in new construction and adaptively reused historic industrial buildings.

2006

Waldo Lofts residences opened, the first new construction inspired architecturally by the Powerhouse within the Powerhouse Arts District.

2009

The first Jersey City Redevelopment Agency-sponsored phase of its bold City Power Powerhouse stabilization program was initiated, leading to the sealing of the building’s window openings and the stabilizing strapping of its central tower. Notably, however, the roof levels of the building were not stabilized as part of the City Power program — a decision that would lead to additional deterioration and damage.

2013

As part of the ongoing City Power program, the Powerhouse’s three surviving smokestacks were demolished with the promise that they would be replicated/rebuilt in the near future when the building is adaptively reused — a promise that the Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy will fight to see realized in the future.

2019

The Oakman residences opened on First Street in the Powerhouse Arts District, named as a tribute to Powerhouse architect John Oakman.

2025

In January 2025 The Jersey Journal published Powerhouse Promise as a final 2-page article by Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy (JCLC) founder John Gomez as the newspaper concluded its 158-year run as Jersey City’s premier newspaper. In the spring The Arts & Powerhouse Building was unveiled in the Powerhouse Arts District as a major adaptive reuse project developed by Kushner and KABR Group with GRO Architects inside two industrial buildings originally constructed over a century ago for the Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company. The new project was awarded the Jersey City Landmarks Conservancy’s prestigious and highly competitive JCLC Adaptive Reuse Award for 2025. In September the JCLC launched its Save the Powerhouse preservation campaign at its annual JCLC Preservation Awards ceremony at the historic Barrow Mansion located in Jersey City’s Van Vorst Park Historic District. With this massive public-spirited movement, the JCLC will continue the Powerhouse battle that started in 1999 with a new sense of hope, confidence and energy.